The watchmakers behind the Henry Graves part 2: inspired by Breguet

Patek Philippe's famous pocket watch produced in the Vallée de Joux was, for a long time, the most complicated ever. The “Star Watch” exhibition in the L'Espace Horloger Museum unveils new data.

So far unveiled correspondence between watchmakers Jean Victorin Piguet and Paul-Auguste Golay has shed some light on the legendary piece. The letters have been publicly exhibited for the first time at the Star Watch exhibition in the L'Espace Horloger museum (Vallée de Joux). Through them, we have now learned that Breguet inspired the creation of the Henry Graves. We are hence talking about a treasure that is now being showcased for everyone to see in Le Sentier until the end of April 2016.

Indeed, in their technical correspondence, the two watchmakers often brought up the “Praslin”. The piece, originally Breguet no. 92, belonged to the Duke of Praslin (1756-1808) before joining the private collection of English collector David Lionel Salomons (1851-1925), who also owned Breguet no.160, aka the “Marie Antoinette”.

Before his death, Salomons gave the Marie Antoinette to the Museum of Islamic Arts in Jerusalem. The Praslin was given to the Arts and Métiers Museum in Paris in 1923.

Some excerpts of the hitherto unknown correspondence

Jean Victorin Piguet to Paul-Auguste Golay, on December 6, 1926

… “We have thus given an approximate price for the Praslin that we are not sure the customer will accept. If he did, we would go to Paris and we believe it would be better if you could come with us, if at all possible. However, we would rather not produce the piece at all, given the kind of work it would entail. We favor more modern pieces, like the few we are already working on and we believe that you are of the same opinion".

As part of his work, Jean Victorin Piguet studied the Praslin, considered Breguet's masterpiece only second to the Marie Antoinette. All throughout his correspondence, Piguet uses Breguet's work as reference as well as a major source of inspiration. Other watchmakers featured too, such as Ferdinand Berthoud and Elysée Golay or Léon Aubert from Vallée de Joux.

The following correspondence extracts provide some insight into the technical and financial issues discussed by the two men:

Jean Victorin Piguet to Paul-Auguste Golay, on July 12, 1927

"Concerning the pricing of these mechanisms, it is essential that the producer is rightfully remunerated. Yet, as you said, we must remain within a certain range that shall not discourage the customer and which will make them come back to us in the future. A week ago, we met Breguet’s current manager... The cost price of the Marie Antoinette is not CHF30,000 but between CHF8,000 and CHF10,000".

…"Does your count of wheels and pinions take into account that, in order to return to the same point every 4 years, the year wheel must make a turn in 365 days and a quarter, so as to compensate for the tooth the star jumps on February 29? Otherwise, after 4 years, the variation would result in March 3 displaying the time of February 29. The error would thus increase more and more.”

Paul-Auguste Golay to Jean Victorin Piguet, on July 9, 1927

… “Did you know that Breguet paid approximately CHF500 for one of these calendars, therefore making a profit of almost CHF1,800?

Whilst I wouldn’t dream of asking for that price, I do hope that you take that into account when negotiating with your customers (you can actually mention that to them if need be) and that you have anticipated a certain margin for unforeseen issues.

Country watchmakers: legendary personalities

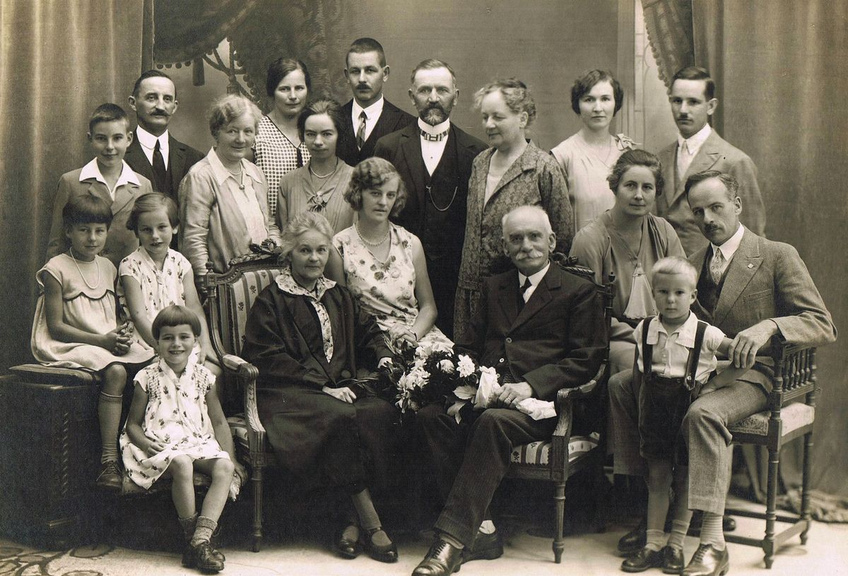

The other men who took part in this project were also prominent figures and representatives of the legendary life led by the country watchmakers of Vallée de Joux. Juste Olivier Aubert (1856-1932) made the winding system of the Henry Graves watch right before his death at the age of 76. He did not have a known ascent. Whether he was abandoned or made an orphan, it would appear he was raised he in a foster home in L'Orient. He started working at the farm at a very young age. It was probably in one of the farms he worked in, where farming was combined with watchmaking in winter, that he learned the trade and became a country watchmaker himself. He married Louise Rochat (1852-1898) and settled with a few cows in a farm in the "darbyste" community in Bioux-Dessous. After his wife’s death in 1898, he married another Louise Rochat with whom he raised the children of his first wife together with the ones from his second marriage.

Juste Aubert had 11 children of whom 7 lived. His eldest son, James Aubert, followed his father's career and opened a workshop in Le Brassus. It seems plausible that James Aubert also worked on the winding system that Victorin Piguet ordered from his father. A humble man, as per the values of his religion, Juste Aubert never stopped repairing the trauma from his childhood by constituting a family to whom he transmitted everything he built throughout his life. Born from his second marriage, Eva Madelaine gave birth to Agnès, who became secretary of Mr. Lugrin at the Lemania factory in L'Orient. She is the one who has today provided all this information about her grandfather, by allowing access to her family archives.

Charles Rochat, watchmaker, preacher and… tooth puller

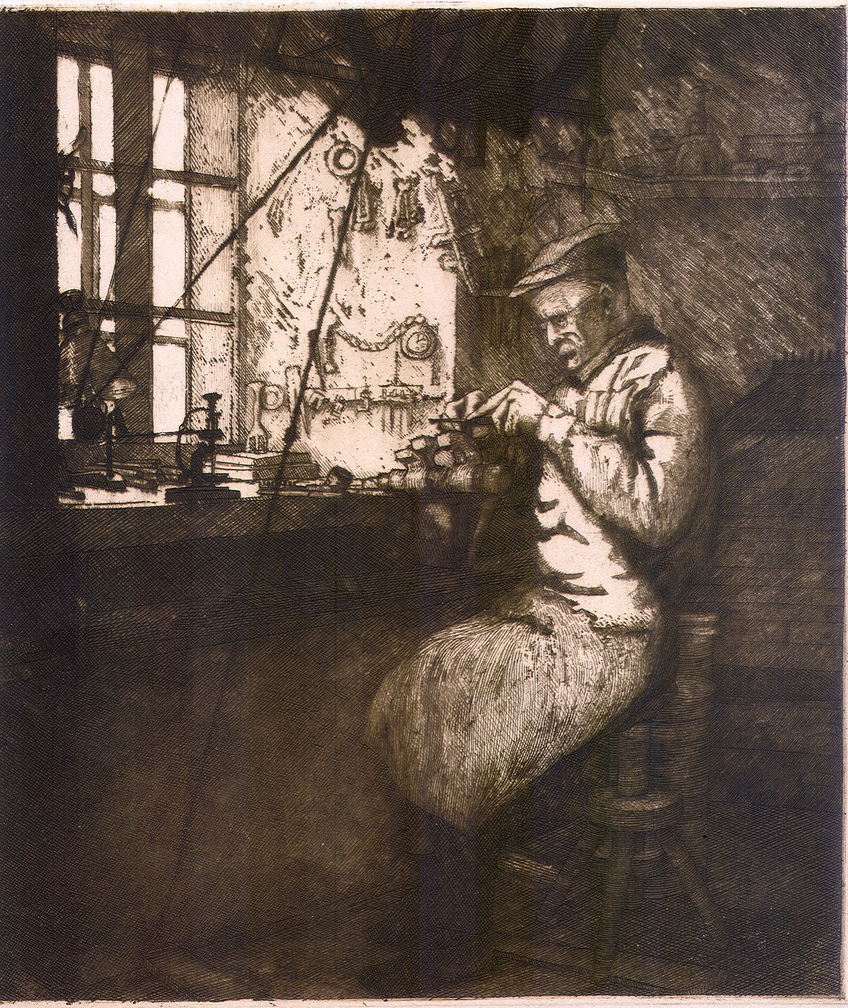

Charles Rochat-Reymond (? – 1941) was another watchmaker who worked with Jean Victorin Piguet. He was also a preacher and a tooth puller! In addition to his work as a watchmaker-turner, he was actively involved with his community in Bioux.

In his watchmaking workshop, he worked on a Jacot tool to carve, using the chisel, tiny wheel axes whose pivots were gauged to the hundredth of a millimeter. It was in this way that he made the wheel axes of both the movement and the chronograph of the Henry Graves. Raised an evangelical Protestant, Charles Rochat was an important man to the "darbyste" community of Bioux. Very committed, he devoted his life to others and his modesty made him a respected man among his contemporaries. His strong convictions and his faith encouraged him to become a preacher. He knew how to guess the problems encountered by others, how to understand them and give them wise advice, using tact and pedagogy.

Charles Rochat was also the telephone man (messenger or correspondent) within his community. He had a telephone at home and carried his neighbors' messages. Finally, he was also the one to go to for “teeth issues”. Claude Bernet's childhood memories, transcribed in his book, give an outline of this part of his life: "Bad teeth, isn't it Charles? Charles heartily nodded. We always ended up opening the mouth. There was half a bar of chocolate on a table. This was still a rare commodity in these times, a soothing and misleading vision. Once the mouth opened, the diagnosis was fast and slightly questionable.

Yet the tooth causing the problem was usually easily spotted by the deep black cavity on it, so any doubts were swiftly erased. It was only at the last moment that the pliers appeared out of nowhere. A powerful hand grabbed your head and it was done! Painful as it was, at least it was quick.” (own translation of an excerpt from the book "La Grande Complication" by Claude Berney.)

Like other multi-function men, David Alfred Nicole, Michel François Piguet, Louis Rochat-Benoit and Luc Rochat also worked on the Henry Graves, following the country lifestyle that was the norm in mountain valleys.

Philippe Dufour: guardian of the "Vallée de Joux way of life"

The reflection of a time and certainly of the roughness of life in a wild and hostile natural environment, this "way of life" was probably more a necessity than a choice. Yet, we do wonder whether that is the case when we meet some independent watchmakers from Vallée de Joux nowadays. Philippe Dufour is known to perpetuate the tradition of the complicated watches from Vallée de Joux. A closer look into his daily life, however, reveals that he also perpetuates the culture and popular traditions often outweighed by the valley’s worldwide reputation for horology.

Philippe Dufour, like other watchmakers from the Vallée, seems to have adopted this lifestyle and made it an inherent part of his individuality and of his watchmaking practice. If he is not at his workbench, then he must be busy in the forest doing his other job at the service of the local community. So, if you want to find him, go to the forest and there you may understand the watchmaking culture of the Vallée de Joux in its entirety!

Philippe Dufour is a member of the watchmaking Commission of the Watch Museum in Vallée de Joux, L'Espace Horloger. It is in this regard that he seized the opportunity to observe the Henry Graves right before it was sold at Sotheby's.

L'Espace Horloger Museum. Temporary Star Watch exhibition (dedicated to pocket watch Henry Graves) - until April 24, 2016

First part of the article: The watchmakers of Henry Graves part 1: history's forgotten contributors

More on the Patek Philippe Henry Graves: