History of architectural watchmaking

Watches have traditionally been the expression of watchmakers’ quest for aesthetics. Here is a historical overview from an architectural point of view, before the designer era.

The basic function of a watch is to indicate time. It thus needs to be perfectly readable. The layout of the components and the architecture of the mechanical movement of a watch were at first dictated by practical considerations. The use of the different functions imposed the shapes of the components, the motor, the dial, and the case. For a long time, watches were round and it seemed that trends of a specific time had little or no influence on this phenomenon. Nevertheless – beyond the practical aspect – watch motors produced in the different manufactures between the late Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution expressed very marked aesthetic research and taste for harmony. Caring for details and aesthetics and the quest for harmony have been central to watch production in Vallée de Joux for a long time.

Watchmakers with signature styles

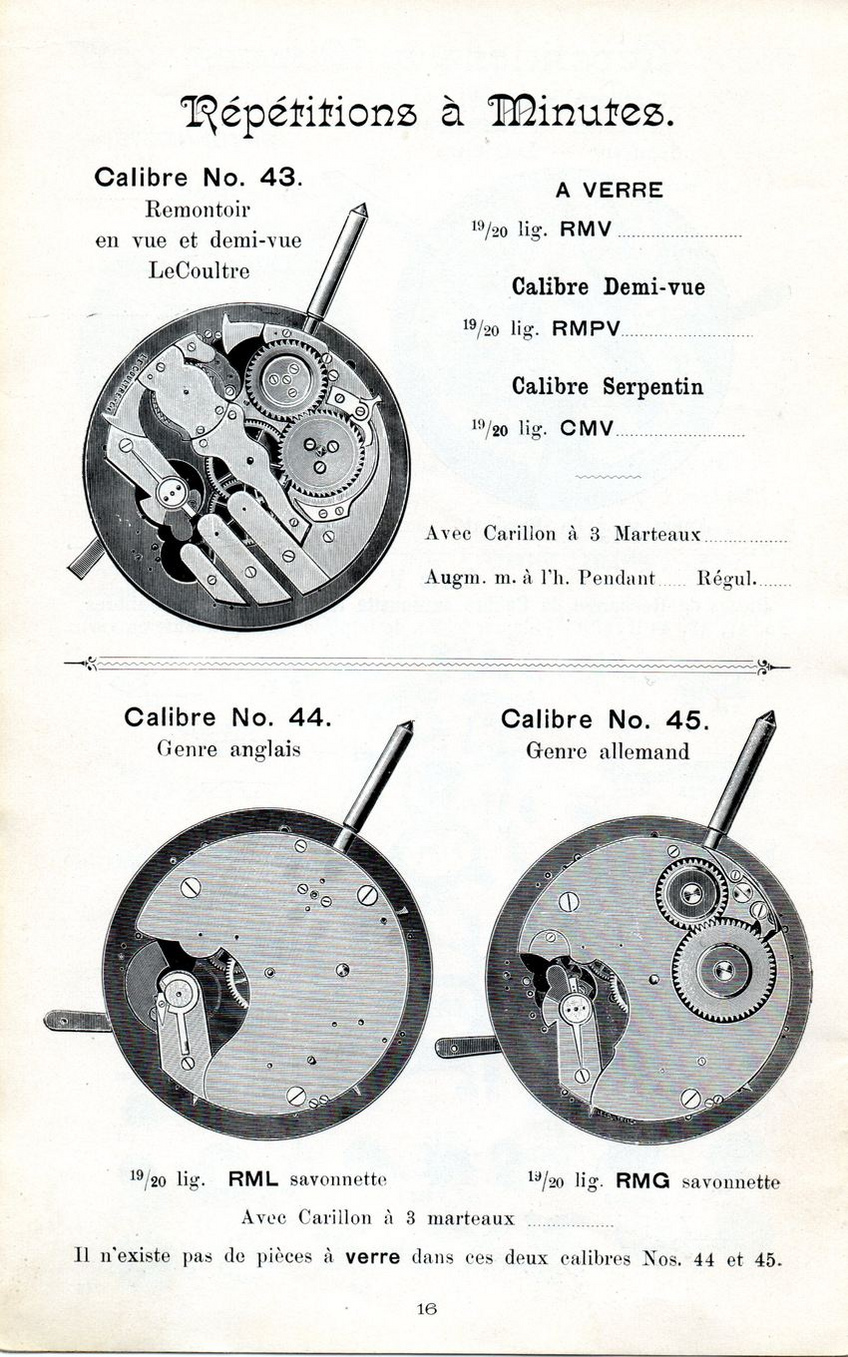

Jean Antoine Lépine’s architectural revolution between 1762 and 1771 was one of the greatest watch architectural revolutions. From 1920, less practical globular or oval shapes were replaced by flat and round watches, easier to pocket or wear on the wrist. Lépine’s style became the standard from the 18th century, but watchmakers’ own artistic touches allowed for watch mechanisms to be identified. Thus, the British and the Germans used an easily recognizable mechanism with a three-quarter-plate bridge. The British version was completely covered whist the German had apertures on the ratchet and the winding crown. In the Swiss version of this mechanism most of the motor’s components were fixed to the plate through bridges (see image) in order to make them visible. These three construction styles were mastered in Vallée de Joux and in the rest of the Jura Arc, which supplied the different watchmaking factories between the 18th and the 20th century. We can go even further and talk about different production styles in Switzerland. In Vallée de Joux, we find LeCoultre’s signature –the serpent-shaped central bridge in its minute-repeaters– Louis Audemars’ signature with the most refined finishes or Aubert’s signature with a central bridge that holds the chiming bridge.

Watchmakers always respected the strength lines of the movements they produced and their timepieces had their own dynamics and gave the illusion of movement. There were spiral chronograph hammers to not break the homogeneity of their round architecture, feeler-spindles of curved repeaters to turn the barrel, heart-shaped triggers to fill a void space and not misbalance the whole mechanism (see image). Once their practical role was fulfilled, the shape of the components’ varied, which could only obey to aesthetic reasons.

The quest for formal harmony

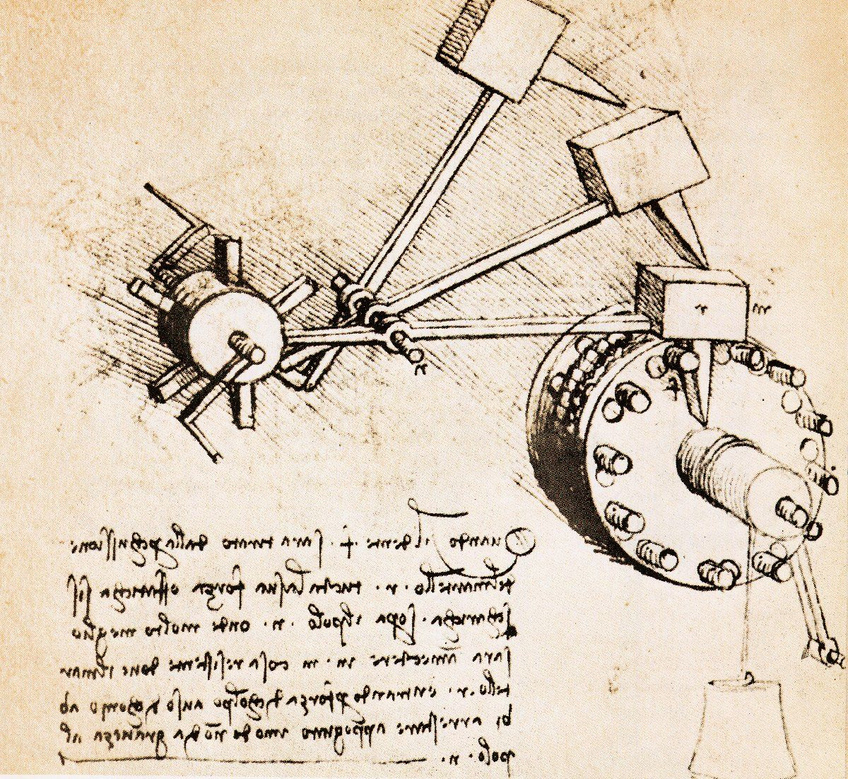

The parent plate – ancestor of technical design – is to the watchmaker what a plan is to an architect. The components’ layout was engraved and balanced according to the space available on the plate. A plate could be used as a pattern for the production of many mechanisms. Even though the plates were most often round-shaped, the parent plates could be square, rectangular or heart-shaped amongst others (see image). The materials and finishes chosen catered for overall harmony. The watchmaker affixed grainings, perlages or Côtes de Genève and applied chamfering, polishing and other treatments on the components.

They took into account the color and layout of the rubies and the thermal-treated blued screws. They also considered all other colors whose use was a matter of choice or necessity. These proceedings strengthened the aesthetics of the watch.

Apart from the practical aspects, the search for harmony pushed watchmakers to balance and embellish their mechanical constructions by playing with shapes, materials, finishes and the layout of components. Technicians at heart, these watchmakers certainly did not aim to be artists. However, their aesthetic sensitivity prevailed before the arrival of fashions and artistic trends such as Art Déco, which revolutionized the shape of watches before the designer era.

The design era

In latin, “designare” means to mark with a sign, to draw, or to indicate. The verb “desseigner” was used in ancient French before being replaced by “désigner” and “dessiner”. The term “design” was coined during the Industrial Revolution.

In 1849, Sir Henry Cole – main craftsman of the London universal exhibition – was the first ever to use the term. In French, the word is synonymous of “industrial aesthetics”. Design is a discipline that consists of designing objects by playing with shapes. It aims to improve human quality of life. Its role is to meet the requirements of everyday life. It takes into consideration aesthetic, functional, technical, legal, economic, social, political and even philosophical aspects. Design is to the industry what art is to craftsmanship. This term was introduced quite late in watchmaking; that is, after the Industrial Revolution. Watchmakers have long preferred calling the concept style, trend, and watchmaking architecture.

Source: "Design-Moi-Une-Montre" temporary exhibition from 29th May 2014 to 30th April 2015, Espace Horloger Vallée de Joux.