The 18th century marking a new era in watchmaking

Based on my experience of nearly a decade in leading houses of the industry, I thought that I knew something about watchmaking until I was drowned into the discovery of the 18th century watchmaking.

Some may think that the 18th century is “just” a primitive approach of watchmaking that merely led to the next century when techniques were further improved. In fact, innovations of the 18th century need to be understood in their much deeper and more complex historical background. During the 18th century, the Enlightenment culminated in the French and American revolutions. Philosophy and science increased in prominence. Combined with the increasing importance of maritime explorations, the connections between watchmaking and politics, including foreign affairs, were strong.

The 19th century, widely providing the ground layer for today's manufacturing, has undeniably brought a number of technical innovations that are captivating. I spent hours reading to try and understand each innovations and their connections to each other beyond physical borders. It is striking to note that in many cases, similar experiences were run in several countries around the same period of time leading to fierce altercations in order to determine who came first.

In the 18th century, watchmaking played a much more vital role meaning that coming up first was not sufficient to reach an expected recognition by authorities.

The great expeditions on land and sea conducted by leading countries set the need for better navigation tools. This marks the beginning of a fierce competition between scientists including astronomers, mathematicians and finally watchmakers.

As it became obvious that the best technique to calculate the longitude and thus position oneself on the globe requires the use of an accurate clock, all efforts were turned towards producing highly precise clocks. In France, after evident failure by the legitimate Academicians, watchmakers were increasingly considered as scientists instead of simple craftsmen and expectations on them became very high.

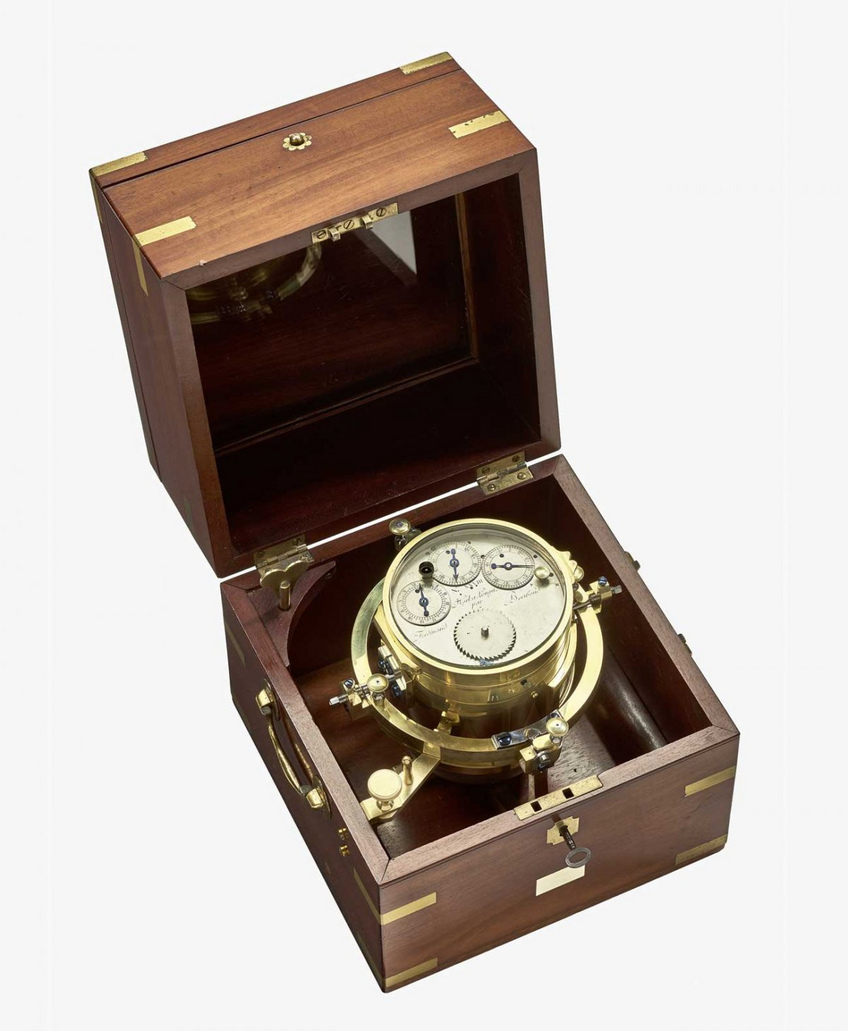

Displaying the time was no longer the main concern but precision of time displayed was now the target taking civil horology a step further with marine clocks becoming navigating tools. Of course, the prizes offered by the English government and later by the French Académie des Sciences influenced this new direction. But the financial reward was only part of the motivation to solve the matter of longitude. Indeed, civil horology was a well-established lucrative business and the motivation for the most talented watchmakers to solve this equation must have been beyond the financial recognition.

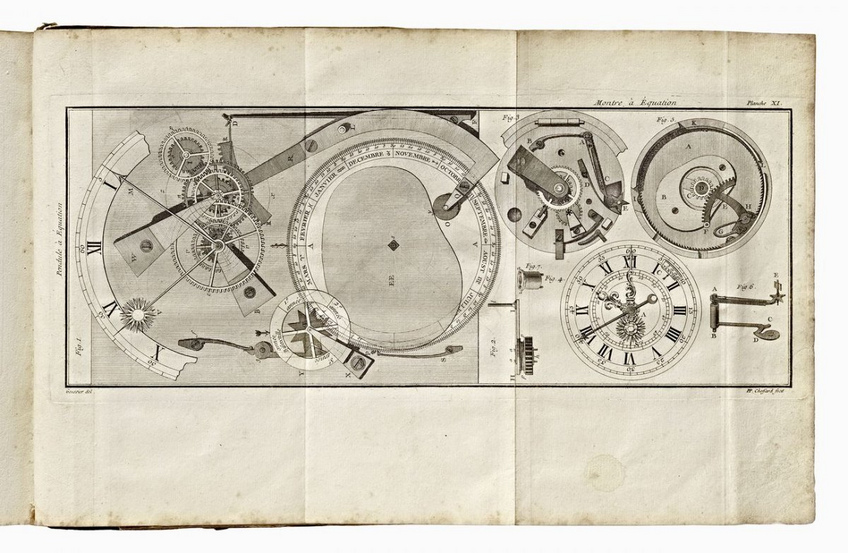

In order to improve precision, all watchmakers worked on solving three key issues:

- Inventing an escapement allowing the balance wheel to oscillate without being disturbed by friction

- Discover how to compensate variations in temperature

- Avoid the functioning of chronometers to be affected by movements on board of ships.

The researches conducted in those three areas resulted in later inventions that could benefit from the key accomplishments consequently obtained as the matter of a global dynamic rather than a single person's devotion.

The most visionary and talented of these watchmakers decided to release their researches in key publications. Browsing the pages, witnesses of those achievements, shows how scientific the approach was leaving no more doubts that nothing there was primitive but rather forward-thinking.

What might have been regretted at the time is that the penetration of this early approach was not as smooth as expected. Considering that these marine clocks represented a major part of the cost of a vessel, you may understand that the investment was not done without a reason.

However, due to its high cost, directly related to low availability as all marine clocks were still crafted by hands, with no industrial approach, it was confined to an elite.

Another difficulty that prevented marine clocks to be automatically carried on board is the heavy burden of tradition. Not only marine clocks were expensive, thus aimed at an elite, but also few sailors were familiar with theoretical navigation, preferring well-established method of orientation, that were also less expensive.

It is only later in the 19th century that chronometer makers dedicated their production to larger standardized production thus decreasing the price per unit and allowing a broader maritime use.

Rediscovering this legacy with today's vision makes even more sense if we consider that these marine clocks were constituting the GPS of the time. Then connected watches could be considered as legitimate heirs of this patrimony.

This fascinating journey just started for me and I look forward to open the second chapter of this forgotten piece of history in order to understand the relative role of each watchmaker and its individual impact on a collective success.

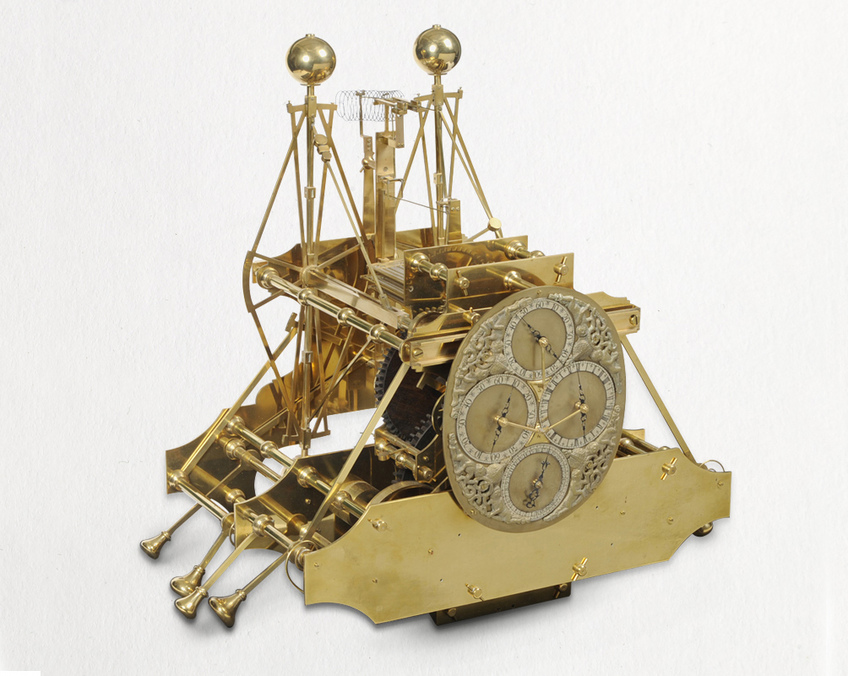

Front picture: Movement of the "Horloge à Longitude XXVIII"