Philip Poniz: High Frequencies In Depth

Philip Poniz, horological historian, Expert-in-Chief at WatchInvest, Inc., where he advises high-end watch collectors and investors, Head Expert at Antiquorum during its glory years, Court Expert and Master Restorer reveals for us all the little and big secrets of high frequencies in watchmaking.

First published on veryimportantwatches.com

Constantin Stikas: What do we gain with a high frequency watch?

Philip Poniz: Reliability of the performance in a sports environment and the ability to read smaller time intervals.

CS: What is at risk with a high frequency watch?

PP: Accuracy in the long run. The higher the frequency, the shorter is the free travel of the balance. As a consequence, the watch will run on not a very detached escapement, affecting its rate.

CS: 4Hz were considered a high frequency at what point in time?

PP: In the 18th century, even 2.5Hz was considered a high frequency. It was John Harrison who, in his famous H4 tested in 1761, used high frequency which then was a balance of 2.5 Hz, and also recommended 3Hz for smaller watches.

CS: In the high frequency sector, there was but a single protagonist since 1969, namely the El Primero, which operated at 5Hz. In recent years, we have seen watches operating at 5, 8, 10 or even, at TAG Heuer, at 50, 500 and 1000Hz! Why allow so much time to pass and create high frequency timepieces only very recently?

PP: This is not quite accurate. The first 5Hz watch had already been created in the 18th century, not long after Harrison’s H4. It was one of the earliest lever watches and was produced by Josiah Emery circa 1770. Clearly, the subject of high frequency watches was evident as early as the 18th century. In the beginning of the 19th century, Edward Massey made a 6Hz timer. 8Hz was patented by William Williams on March 26, 1890, years before Zenith.

The Continental counterparts did not lag far behind. In 1848 Louis Moinet published his Treatise, in which he stated that “a few years ago” he had produced a timer running on a 30Hz balance. It has been assumed that by “a few years” Moinet could not mean more than eight years. Consequently, everyone assumed that the manufacturing date was not earlier than 1840. The instrument was discovered recently and to the astonishment of everyone it appears that the hallmarks indicate the date to be before 1816. The end of the 1800’s saw 50Hz timers developed by Nicole Nielsen, or rather, improved from their previous 10Hz ones. The early 20th century Swiss makers of high frequency watches, such as Ed. Heuer, had a well paved road leading to the introduction of the Micrograph.

I do not want to get into details about why brands are interested in high frequency today. There are two parts to this question. Firstly, technical difficulties (which I will explain later in the interview) and, secondly, the realities of today’s market.

CS: What else do you think of the Louis Moinet timer?

PP: I would like to be able to examine the case and the return-to-zero mechanism closely.

CS: The El Primero is a movement that hundreds of thousands of people have been wearing on their wrist already for 44 years, while all the other high frequency watches, and especially the TAG Heuer, are champions in the field and are what we would term ‘concept watches’. What do you think about the difference between an everyday watch and a concept watch?

PP: Ordinary mechanical watches are becoming a thing of the past. Those who want just a timekeeper on their wrist buy quartz. Today, a mechanical watch must be a ‘concept watch’, must show an innovation, mystery, beauty, or another remarkable achievement; otherwise the mechanical watch industry will cease to exist.

CS: During the presentation of the TAG Heuer Mikrotimer, someone asked if the eye, the hand and the brain are capable of keeping up with such an astounding performance (1/1000th of the second). What are your thoughts on this? Are there any limits to innovation?

PP: Yes, certainly there are limits. Let’s analyze the anatomy of a simple chronograph, the time wasted while timing an event using a mechanical chronograph:

1. The human delay from the moment of making the decision to activate the chronograph, to the moment this instruction reaches the finger ordering it to push the pushbutton.

2. The delay between disengaging the hammer and engaging the clutch wheel.

3. The delay caused by the imperfections in the chronograph wheels, i.e. when the clutch wheel is engaged it does not apply torque to the chronograph wheel instantaneously. First it must get rid of the idle space between its teeth and the chronograph wheel teeth.

4. The human delay, as in (1) during the stopping.

5. The inertia of the chronograph wheel at the moment of disengaging the clutch. When the clutch is disengaged the chronograph wheel still turns by its inertia. The wheel has a friction spring which slows the inertia but it does still exist.

6. The delay between disengaging the clutch and engaging the stop (brake) lever.

7. The bouncing effect of the stop lever. If you film the chronograph action with a high speed camera, you will see that when the stop lever is released it hits the chronograph wheel and bounces back, much like a steel rod hitting on another metal. The tension spring dampens the bouncing but it exists. During the bouncing the chronograph wheel is not stationary. There is a similar phenomenon in the lever escapement when the escape tooth hits the pallet, but the effects are not important because they do not affect the balance, which swings freely during the bouncing.

CS: And what is the role of high frequencies in the quest for the improvement of the precision of a mechanical watch?

PP: The quest stopped at 5Hz in terms of improving the long-term precision of a watch. As of now, it improves the precision of the measurements of small time intervals.

CS: Roger Dubuis presented the Excalibur Quatuor model beating at 16Hz (4 balances of 4Hz each). What do you think about this?

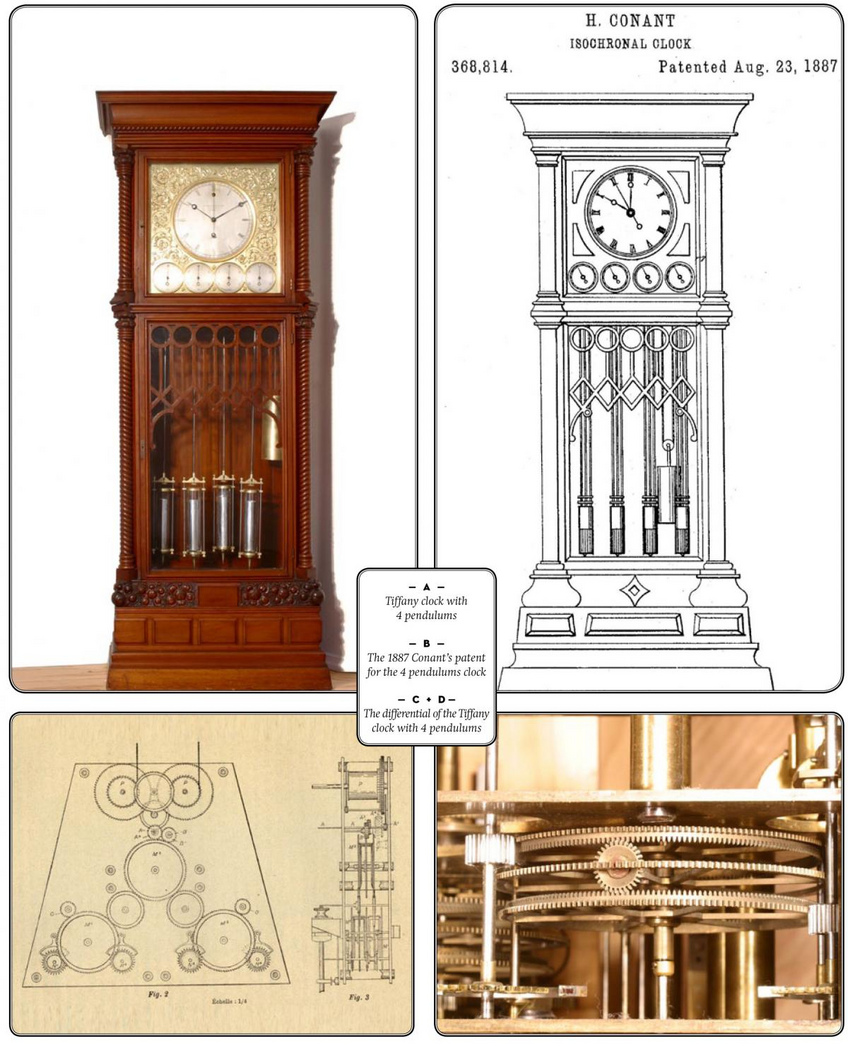

PP: I have the Quatuor predecessor – a four pendulum clock with a differential mechanism, like the Quatuor but made in 1887. It was made by Tiffany’s in accordance with Conant’s 1887 patent. It is considered the most important regulator ever built on American soil. I would enjoy wearing a differential four-balance wristwatch and to be able to check it against its older brother – the most sophisticated and remarkably accurate four-pendulum differential clock built 126 years ago.

CS: Maximilian Büsser stated in his interview that “…after the ‘70s and the invention of quartz, the mechanical movement has ceased to have any reason for existing… In Watchmaking, we can state that in the era of the TGV we are making steam engines. Therefore, when we move from 5 to 6, 8 or 10 Hz, (and I am not talking about 500 or 1000Hz), it is the same as if we were straining to make a steam-powered engine that is 5 or 10% faster than its counterpart…” What do you think about this?

And after that, Jean-Pierre Musy, Patek Philippe Technical Director, replied to this remark by Maximilian Büsser: “When we see high-quality watches, they have a chronometric bulletin, COSC values, meaning –6 to +4. There is a daily deviation of 10 seconds! In any case, it is significant, 10 seconds per day, this amounts to nearly one minute every minute! Do you believe that there is nothing to be done? I believe that there is something to be done! There is work to be done in order to improve this situation. We cannot allow ourselves to make watches that have upwards of a one minute error margin within the space of a week! The mechanical watch must be more accurate than that!” What is your opinion about this?

PP: This is a question similar to “Since helicopters are capable of reaching Mt. Everest, do you think there then will be no interest in climbing it?” Of course, there is continued interest. The same principle applies to watches. Mechanical watches have soul; quartz watches do not. This has been true since the time of the Renaissance.

Actually, here history repeats itself: during the Renaissance the mechanical clock or watch was an object of fascination, an object upon which a hand was placed in official portraits, the pride of towns and wealthy owners. None of this was because of its timekeeping ability. A sundial was more reliable. In fact, it was a sundial that a mechanical clock was set by. Yet, our ancestors valued the less accurate mechanical timepiece much more. As we do today.

Regarding the second part of the question, a mechanical watch can be made much better than having a 10 sec. daily variation. In fact, many are. But many are not. It is a matter of economiIt is a matter of how much hand-finish of the final adjustment, after automatic production and/or automatic assembly, the company is willing, or able, to do.

CS: To most people, Switzerland is a ‘slow’ country. However, the CERN is located in Switzerland and today we see the Horlogerie sector breaking the high frequency record at regular intervals. What is your opinion on this?

PP: The Swiss have changed. Last year they ranked as the most adaptable country among all industrial ones.

CS: What is your personal relationship to speed?

PP: I love skiing fast. But even more so, I want to have full control of how and where I am going.

CS: Do you think that a speed limit should be imposed on motorways and, if so, at how many km/h should it be set?

PP: Today, living in the United States, driving through Utah or Nevada’s desert on a straight highway with visibility for kilometres, and no other car on the horizon – having a speed limit is crazy.

I would like to be able to drive as fast as I want on highways not only in Nevada, but I know too many people who, if allowed to do so, would crash, possibly into my car.